|

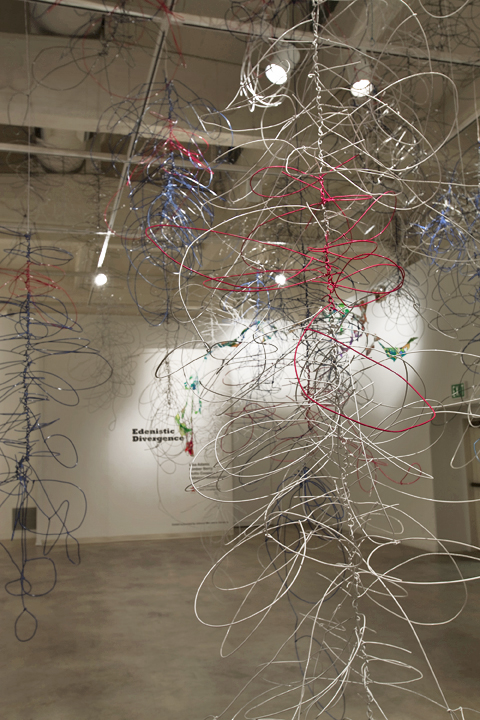

A Little Bit of Narcissism is a Good Thing, 2009 plastic insulated copper electrical wire site-specific installation overall: 336 x 377 x 200 inches |

| |

| Edenistic Divergence catalog essay by curator Andi Campognone The landscape has been depicted by artists since ancient times. It was a popular motif amongst the Greeks and Romans, as the recent Los Angeles County Museum exhibition “Pompeii and the Roman Villa” demonstrated, and provided important background for religious and figural paintings up through the 15th Century. Dutch painters popularized landscape as a subject in the following two centuries, but it was not fully accepted as an independent genre until late into the 1700s. As painting techniques changed during the Industrial Revolution, so did landscape painting: it was less and less a realistic record and more and more a spiritual, optical, or formal re-interpretation. Now, landscape painting is a means for artists to express their fears and concerns about our increasingly stressed environment. In response to these fears and concerns, the painting, sculpture and installation work in Edenistic Divergence addresses the changes we anticipate to our landscape as a result of pollution, global warming and genetic tinkering, doing so through the contemporary use of color and material. Specifically, the landscape here becomes both subject and background for a symbolic re-creation of Eden. Greco-Roman courtyards of the First Century were adorned with elaborately painted landscapes. These outdoor rooms, which served as places of leisure and contemplation, were often decorated with animals, especially birds. In similar fashion, Lisa Adams creates realistic portrayals of birds and small animals in fantasy landscapes of their own. (Adams even references a volcano in her painting, Convocation, bringing to mind the Vesuvian eruption that buried Pompeii.) Adams’ paintings capture the past while visualizing the future. Beyond the evocation of sky and weather, the scale of the paintings brings the eye into the two-dimensional landscape as if it were three-dimensional – a suggestion of the trompe-l’oeil the ancients admired so much. Adams’ art gets an optimistic charge from its colorful palette and playful placement of subjects, but lends itself to serious contemplation –perhaps of “life after Man.” Impressionist landscape painting was characterized by, among other things, visible brush strokes, open composition, and an emphasis on light in its changing qualities, tending to indicate a passage of time (as seen in Monet’s famous Waterlilies). Kimber Berry’s work, without the brushstrokes , effectively portray such temporal passage without the use of recognizable subject matter, or feathered brushstrokes, but do address some of the same issues as found in Monet’s paintings, including the employment of unusual vantages and movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience. Paint appears to flow from up and over the wall in a massive waterfall of color. Pigment is in constant movement. The artificial palette, hardly the color of life-giving water, captures our attention with its vibrancy, and then reminds us of its toxicity. Hollis Cooper‘s work reflects these same characteristics in a more conceptual way. Also manifesting the passage of time and employing unusual angles, Cooper’s acrylic vine grows and changes, apparently living and breathing the length of the gallery. This futuristic vine also boasts a cautionary palette, and appears at times to be almost mechanical. Artists are at least as concerned as the rest of us over environmental byproducts of the Industrial and even Green “Revolutions,” including acid rain, chemically treated soil and plants, and the consequences of genetically altered fruits and vegetables. These factors, and especially the constant worry they cause us, take form in Rebecca Niederlander’s wire cloud installation. Constructed literally of heavy metal, the dense, intricate structure hovers, an ethereal black cloud, over much of the exhibit. The word “landscape” comes from the Dutch landschap, which means sheaf, or a patch of cultivated ground. Edenistic Divergence symbolically and literally represents a patch of ground cultivated with important traditional elements of landscape art, including sky, weather, flora, and fauna. With more than an incidental nod to art history, the four artists in Edenistic Divergence cultivate their ground into compelling interpretations of the land, past, present and future. | |

| |

| |

| |

|